Know the Signs of EPM, a Master of Disguise

In addition to an altered gait, horses with EPM can have paralysis of muscles of the eyes, face, or mouth, evident by drooping eyes, ears, or lips.

Photo: Noah D. Cohen, VMD, PPH, PhD, Dipl. ACVIM

Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM) is a debilitating neurologic disease that cannot be ignored. More than half of all horses in the United States—and in some areas as many as 90%—have been exposed to the disease’s causative agents. Its ability to masquerade as other health issues, such as lameness or other neurologic diseases, can make it difficult to diagnose. While Sarah Reuss, VMD, Dip. ACVIM, of Merial Veterinary Services, says some horses exposed to EPM’s causative agents will not develop the clinical disease, horses under stress are more likely to show signs. In some cases, horses can even be infected without showing signs for months or years or ever. When horses do show signs, it can go misdiagnosed because it can slowly progress and infect any portion of the central neurologic system, mimicking other conditions. Left untreated, EPM can lead to permanent damage. Reuss emphasizes the importance of early detection by horse owners and farm managers, veterinary diagnosis, and an effective treatment plan. “These are the keys to stopping the progression of the disease,” she says. “The faster treatment begins, the better the chance for the horse to recover.” How Does a Horse Get EPM in the First Place? It starts with a protozoal parasite, most commonly Sarcocystis neurona, via the opossum after it ingests contaminated tissue from intermediate hosts such as the armadillo, skunk, or raccoon. In its infective stage, the sporocysts are passed through the opossum’s feces, which the horse comes into contact with as he grazes or eats or drinks contaminated feed or water. Once consumed, the sporocysts travel from the intestine into the bloodstream and cross the blood/brain barrier where they can cause inflammation and damage the horse’s central nervous system. Researchers now know that a second organism—Neospora hughesi—can also cause EPM, however this protozoan parasite’s life cycle is less well-understood. Early Diagnosis is Crucial “EPM can evolve slowly or present suddenly with varied signs from mild to severe,” Reuss says. There are several factors that can determine its progression and severity, including:- How long the horse has been infected;

- The points in the brain or spinal cord where the sporocysts have infected; and

- Stressful events during EPM infection.

- Incoordination, weakness, and/or abnormal gait;

- Muscle loss on one side, usually along the topline or the hindquarters;

- Paralysis of muscles of the eyes, face, or mouth, evident by drooping eyes, ears, or lips;

- Loss of sensation of the face;

- Difficulty swallowing; and

- Head tilt with poor balance—the horse might assume a splay-footed stand or lean against stall walls for support.

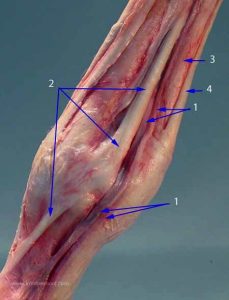

There are two noticeable grooves in the lower leg.

1.) Between the flexor tendons and suspensory ligament.

2.) Between the cannon bone and suspensory ligament.

The vein/artery/nerve run in the groove formed between the flexor tendons and the suspensory. (The groove I have labeled as number 1.)

The veins, Arteries and Nerves (VAN) are bundled together. When you take the digital pulse, it is blood flowing through the artery that you feel.

There are two noticeable grooves in the lower leg.

1.) Between the flexor tendons and suspensory ligament.

2.) Between the cannon bone and suspensory ligament.

The vein/artery/nerve run in the groove formed between the flexor tendons and the suspensory. (The groove I have labeled as number 1.)

The veins, Arteries and Nerves (VAN) are bundled together. When you take the digital pulse, it is blood flowing through the artery that you feel.

This is an enlargement showing the :

This is an enlargement showing the :

Don’t confuse the VAN (1) with the

extensors branches of the suspensory ligament (2).

The ligament will be much harder and towards the front of the leg.

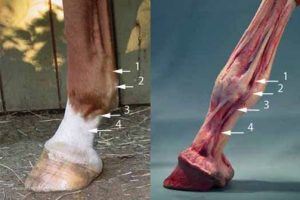

I have asked many professionals to show me how they take digital pulses and have found that everyone has a favorite region on the leg.

After polling many professionals,

4 areas were the most popular for finding the pulses.

Don’t confuse the VAN (1) with the

extensors branches of the suspensory ligament (2).

The ligament will be much harder and towards the front of the leg.

I have asked many professionals to show me how they take digital pulses and have found that everyone has a favorite region on the leg.

After polling many professionals,

4 areas were the most popular for finding the pulses.

If you are comfortable with finding pulses, then using your fingertips is the most sensitive way to check pulses. Usually, I am just checking whether the pulses are strong and bounding, so I lay my fingers over the whole area. It can be faster an accurate enough on a wiggly horse.

If you are comfortable with finding pulses, then using your fingertips is the most sensitive way to check pulses. Usually, I am just checking whether the pulses are strong and bounding, so I lay my fingers over the whole area. It can be faster an accurate enough on a wiggly horse.